by Paul Fitzgerald and Elizabeth Gould

Is not the Pashtun amenable to love and reason? He will go with you to hell if you can win his heart, but you cannot force him even to go to heaven – Badshah Khan, Pashtun tribal leader – a peer of Gandhi – started Afghanistan’s indigenous non-violent movement known as the Khudai-Khidmatgar

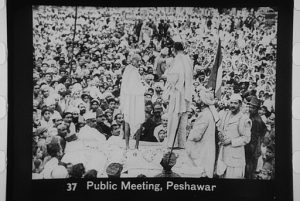

Gandhi at Peshawar meeting with Badshah Khan in 1938 Image by Scanned by Yann Details DMCA

If anyone today could name a historical figure connected to the origin of non-violent resistance against political oppression, it would most likely be India’s Mohandas Gandhi.

Gandhi virtually defined the idea of non-violent resistance in his struggle to free India from British colonial rule. But in 1929, a Pashtun tribal leader in nearby Afghanistan named Bhadshah Khan – a peer of Gandhi – became an important ally by inaugurating Afghanistan’s indigenous non-violent movement known as the Khudai-Khidmatgar – the servants of God.

Since Khan realized that God needed no service he decided that by serving God they would in fact be serving humanity and set out to remove violence from their ancient Pashtun tribal code. Known as Pashtunwali, Afghans had lived by the code’s elaborate rules for millennia and continue to order their lives by it to this day.

In addition to establishing a leadership council accepted by the community, Pashtunwali laid out in detail the proper behavior for hospitality as well as what was necessary to create security for all including how and when the act of revenge was acceptable.

Following Britain’s colonization of Afghan tribal lands east of the Hindu Kush Mountains in 1848, these principles of Pashtun law were gradually replaced by a new British colonial order. Pashtun society was already known to be in need of social reform for its long-standing acceptance of revenge killing. But the British creation of a small, elite landlord-class to control and administer the province turned revenge killing into a permanent blood bath.

According to Dr. Sruti Bala of the University of Amsterdam: “With traditional tribal authority diminished, this ruling elite gradually emerged as a group of powerful landlords who fought among each other and increased rivalry among the clans. By introducing their own manner of punishment and control, including fines, levies, and even imprisonment, they created a new culture of conflict with its own rules of the settlement.”

According to Bala “this was a major change in comparison with the tribal councils’ traditional focus on limiting conflicts and blame, and resolving feuds without punishment.” The 1872 Frontier Crimes Regulation Act further worsened the situation by sanctioning punishments and mass arrests without trial and legal support and placed heavy restrictions on the free assembly of ethnic Pashtuns. The Frontier Crimes Regulations were far stricter in the Pashtun territories than in any other part of British India and directly limited civil liberties.

According to Bala, “The infringements on civil as well as basic human rights were legitimized by the apparent need to control the Western frontier as a defensive line against Russian aggression and military advances in the region.” And this was of course long before the threat of Soviet communism ever existed.

British competition with Russia for control of Central Asia was a central feature of 19th-century imperialism known as the Great Game. Over time a delicate balance was reached and Afghanistan was used as a buffer state between empires but not without a brutal suppression of the Pashtun tribes by the British.

Khan’s appeal to non-violence was accepted by many Pashtuns as a way to resolve deep-rooted social problems while undermining British authority at the same time.

Although organized like an army, his recruits swore an oath to renounce violence and to never so much as touch a weapon. Over time, the Khudai-Khidmatgar movement developed an educational network to address the social and cultural reforms needed to leave revenge and retribution behind and move towards non-violent development.

This network served the community by focusing on education for all, encouraging poetry, music, and literature as avenues of expression that would help eradicate the roots of violence that had become normalized among Pashtuns during British rule.

The non-violence base of the Khudai-Khidmatgar not only addressed the imbalance created by tribal feuds, it also brought Afghans under the single platform of non-violence which ultimately helped the Pashtuns present a powerful united front against British imperial designs.

Khan was an active member of the Indian National Congress, Chief of the Frontier Province Chapter of the Congress, and a close ally of Gandhi and when they first met he questioned Gandhi about something that troubled him. “You have been preaching non-violence in India for a long time,” he said. “But I started teaching the Pashtuns non-violence only a short time ago, yet the Pashtuns seemed to have grasped the idea of non-violence much quicker and better than the Indians. How do you explain that?” To which Gandhi replied, “Non-violence is not for cowards. It is for the brave and for the courageous and the Pashtuns are brave and courageous. That is why the Pashtuns were able to remain non-violent.”

Gandhi’s response to Badsher Khan’s question defined the Khudai-Khidmatgar accurately, but a true understanding of the Pashtun non-violence movement only begins there.

The strength of Badsher Kahn’s Khudai-Khidmatgar and its philosophy challenged more than just the Afghan tribal code of Pashtunwali and the dominance of the British Empire in India. Badsher Khan also challenged the idea expressed by many Western orientalists that his movement was just an aberration.

As we discovered in writing our book Invisible History: Afghanistan’s Untold Story, getting an authentic picture of Afghan culture through the minefield of orientalist scholarship is no simple task. Sruti Bala’s 2013 article in the Journal Peace and Change points out that commentaries and studies of anything regarding the Afghan non-violence movement are “ridden with interconnected problems” that make it impossible to come anywhere close to an honest understanding of Badsher Khan’s movement.

Cultural stereotyping of Pashtuns, labeling acts of non-violent resistance as simply an aberrant phase of an inherently violent culture and denying the indigenous Afghan roots of the movement are just the start. Added to that is an intellectual prejudice that privileges elitist viewpoints of Gandhi’s Hindu non-violence movement over the actual concrete acts and practices of the Muslim Khudai-Khidmatgar.

The maltreatment of the Afghan nonviolent movement reveals more about the biases of Western academics than of the movement itself and according to Sruti Bala has completely obscured its place in history. She writes:

“The social and political movement that this organization spearheaded is arguably one of the least known and most misunderstood examples of non-violent action in the twentieth century. The lack of extensive research is partly connected to the systematic destruction of crucial archival material during the colonial era, as well as by Pakistani authorities following independence.”

Why was the non-violence movement of Mohandas Gandhi awarded recognition and international celebrity status by the West; while the Pashtun Khudai-Khidmatgar movement and its leader Badsher Kahn were suppressed, imprisoned and eventually outlawed? Should the Afghan non-violent movement be dismissed as just an aberration as critics say, or is it more likely that Badsher Khan’s commitment by Pashtuns to internal tribal reform and genuine non-violent resistance was something the British Empire feared might actually change the game and so, did everything in their power to erase it from the public’s memory and pretend it never existed?

Dr. Sruti Bala provides some clues about Badsher Khan and the suppression of the Khudai-Khidmatgar. “Khan belonged to a comparatively well-off land-owning family. Unlike Gandhi or Nehru, he was neither a man of Western learning nor a prolific writer.” She writes. “In fact, he was described as, a man of very large silences,’ a nationalist leader whose life of ninety-eight years, one third of which was spent in jail, is steeped in myth and legend.”

“Khan spent nearly thirty-five years of his life in prison for his political activities and involvement in civil disobedience actions. The British and later the Government of Pakistan systematically destroyed most documents and material records of the movement by raiding homes and confiscating anything related to the Khudai-Khidmatgar from handkerchiefs to uniforms and flags to copies of the movement’s journal.”

The treatment of Badsher Khan was an extreme example of British colonial brutality that left a mark on an Afghan society that remains to this day. But as Sruti Bala points out, without taking these aspects of Pashtun history into consideration it is easy to fall into the orientalist discourse of viewing Pashtun culture stereotypically as one that intrinsically values brutality and revenge.

According to Bala, Indian nationalism also played an important role in perpetuating the image of the brute Pashtun, while never acknowledging or mentioning its own role in sustaining a racist Pashtun narrative. As an example, the Indian bourgeoisie were quite prepared to participate in the structural and institutional violence of the Frontier Province and eager to gain favors from the British.

And then there is the Pashtuns’ own complicity with the narrative through their service to the Empire. “The British ruled the Pashtun provinces through rich and influential landlords.” Bala writes. “One of the most prestigious regiments in the British Indian Army founded in 1847 was the Corps of Guides with a significant Pashtun presence. Many of the activities of the Khudai-Khidmatgar were thus addressed as much against Pashtun collaboration with the British, as directly against British colonial laws.

Yet without exception, the old stereotype continues to rule. Every historical account of the Khudai-Khidmatgar always begins by highlighting Pashtun culture as violent and vengeful, instead of portraying it as a culture living on the borders between civilizations under constant threat to its survival and forced to defend itself… Why is this so?

Again according to Bala, “Gandhi’s speeches to the Pashtuns on his visits to Khudai-Khidmatgar camps reveal a clear mistrust of Pashtun nonviolence which can be traced back to both a suspicion of the lower class Khidmatgar’s soldiers’ inability to embrace the ‘HIGH’ ideals of nonviolence as well as a subtle anti-Muslim slant in his perception of the Pashtuns.”

So despite overt proof of the Khudai-Khidmatgar’s commitment to nonviolence, Ghaffar Khan’s movement continued to be subjected to Gandhi’s personal mistrust of Muslim values and specifically his class biases.

“For the Khudai-Khidmatgar” Bala writes, “nonviolence was not a matter of individual soul-searching and achievement, but a principle for the entire community, requiring a collective effort. This is why I believe the Pashtun interpretation of nonviolence is very different from the individualistic approach that Gandhi adopted.”

And so in this is to be found a profound difference between the Afghan and Indian concepts of nonviolence and perhaps the key to their success or failure as peace movements. According to Bala, Khan is generally placed in the shadow of Gandhi, often referred to as his pupil or even more patronizingly as the Frontier Gandhi. They were good friends, shared similar views on civil disobedience, spent significant time working together, and held each other in high regard. But, in terms of serving as a movement whose ideals for peace could be made universal, it would seem that it was Gandhi’s appeal to the West’s upper-class elites that won him success even though Badsher Khan would have served as a more realistic, grassroots hero for a world in dire need of workable community-based formulas for peace.

Yet largely because of Gandhi, Badsher Khan’s movement remains viewed as just a poor provincial attempt at replicating his ideology and not a genuine indigenous movement of its own with its own characteristics. During his visits to the service and training camps of the Khudai- Khidmatgar, Gandhi insisted on incorporating his personal ideas such as vegetarianism, fasting, and hand spinning (Khadi) into their social reform activities in order to instill what he believed was a “true” sense of nonviolence in the soldiers of the Khudai-Khidmatgar. But for Gandhi to make his specific personal religious preferences a gauge for the purity of Pashtun nonviolence, he risked removing his philosophy from the realm of a cultural movement and placing it firmly into the realm of a personality cult.

According to Bala, references in Khan’s biography indicate that such missionary attempts at making Pashtun practices palatable to liberal upper caste Hindu sensibilities were often met with mild derision. One Khudai-Khidmatgar leader remarked that he had no objections to eating vegetarian food in Gandhi’s ashrams, but wished the Gandhians would not be so fussy when they came to the Frontier Province themselves.

But yet, the sense of Gandhi’s moral superiority was no laughing matter when it came to the plight of the Pashtuns under British rule. In an October 1938 speech to Khudai-Khidmatgar rank and file members, Gandhi announced openly that the Pashtun’s commitment to peace was incomplete. He then proceeded to refer to the idea that Pashtuns – who held life so cheap and would have killed a human being with no more thought than they would kill a sheep or a hen, could at the bidding of one man lay down their arms and accept nonviolence – AS A FAIRY TALE.

Gandhi made his apartness from the common Afghan man and woman, landed or landless a hallmark of his speeches. Reading them today betrays a racist sensibility and a disregard and prejudice for the detail, history, and context of Pashtun life that has been systematically carried forward into numerous current high-minded but failed social experiments.

Gandhi’s disrespect for the elaborate system of Pashtun tribal rules known as Pashtunwali is troublesome. More troublesome still is that multiple generations of historians and journalists have looked to Gandhi’s Pashtun stereotype as the end-all and be-all to the history of the Khudai-Khidmatgar. Badsher Khan understood more than anyone the need to disassemble and delegitimize the acceptance of violence within the context of Afghan society as a prerequisite for creating an authentic peace movement. It is that model inspired by Badsher Kahn that should comprise the next stage of a global movement that removes the impetus from the elite and places it in the hands of the people. And only by doing that can a genuine peace movement move forward.

This Paradigm is Ending: What Comes Next? A FREE Zoom Event Wed. October 12, 2022 3:00 – 4:30 pm/EST RSVP Required at Valedictiondotnet/eventlist

Copyright © 2022 Fitzgerald & Gould All rights reserved – Sourced From: A Declaration of Human Rights for the 21st century World Peace Proposal